Preface

$107 billion.

Around the world, digital marketers are allowing $107bn in revenues to slip through their fingers, every single year. One hundred and seven billion.

Just like any number ending in billion, it’s difficult to comprehend the magnitude of that figure – but to put it in context, at time of writing that equates to just shy of 1% of the total global economy.

You might think that adding 1% onto global GDP would require enormous levels of marketing expertise, effort & expenditure to pull off. But in this case, you would be mistaken.

What is the problem? Why are advertisers falling foul of it? And what can you do to claim your share of the $107bn? These are the principal questions that this paper sets out to address.

The origins of the $107bn gap

By our best estimates, 27% of all media spend delivered on Google Ads is constrained by budget. And what’s more, sources in Google would suggest that an entire 80% of advertisers – if not more – operate with at least one of their campaigns being regularly budget constrained.

For as long as time can remember, marketers have been calling for more budget. But in the world of search, being budget-constrained has a precise definition. It means that your campaign budgets are set too low relative to your bids, or vice versa.

In a marketing channel that is inherently linked to consumer intent, this is a bad thing. Budget constraints carry with them two very real ramifications for the performance you can extract from the channel.

First of all, it artificially limits your addressable target market. By limiting yourself with budget caps, you prevent yourself from entering into certain auctions throughout the day, despite consumers in those auctions displaying high intent for your products. Has a CMO, CFO or CEO ever said “I wish we operated in a smaller market”? No? Well, by being limited by budget, you are doing exactly that – transporting yourself to a smaller neighbouring market.

An often-quoted analogy to budget constraints is that of the closed shop. Imagine operating a retail store on Oxford Street. You’ve paid your staff for the entire day, you’ve got plenty of stock remaining, and you find yourself doing a roaring trade. And then, at some point in the early afternoon, you decide you’ve done all of the business required of you for the day, so you’re packing up early and going home. Every prospective customer who arrives later on will be turned away at the door. Clearly, this would never happen – and if it ever did, the store manager responsible would be fired the next morning. However, this is exactly what is playing out in more than 80% of Google Ads accounts all around the world today.

The second consequence is that, for the clicks you do capture, you end up paying higher CPCs than you could have otherwise gotten away with. The explanation for why this is the case is slightly more technically involved, so if you need a little more convincing, then feel free to skip ahead to the appendix before jumping back up here.

Despite first appearances though, this paper is not a recommendation to carte blanche spend more in search. Instead, this is a call to think more critically about the processes you use to assign your PPC spend in the first place.

Why advertisers fall into this trap

The two modes of budgeting

Consider the two prevailing methods that businesses employ to determine their budget allocation for paid search.

On the one hand we have what might fairly be described as the “Traditional” approach to media budgeting in which, prior to the start of the month, you allocate a fixed budget to every single channel. You’ll also have a fairly strong idea of the returns that you can expect to see from that fixed investment.

The second method is one that has come to be known as the “Demand-Led” approach, in which you don’t really enforce a budget at all. The Demand-Led mindset says “we’ll spend as much as we can, so long as our performance stays within some pre-determined efficiency constraint – such as CPA or ROAS.” Your actual spend will then fluctuate up & down, in line with the ebbs and flows of the market.

In the Demand-Led approach, it’s easy to see that we can avoid the pitfalls of budget constrained campaigns entirely. If there isn’t a rigid spend limit in place for you to hit, then you can set your campaigns up with almost arbitrarily high budget caps. That doesn’t mean that you will actually spend a near-unlimited amount, because the budget cap is a cap – not a target. Your actual spend will always be constrained by the search demand that exists in the market.

Therefore, it’s not up for debate which of these two budgeting methods leads to the stronger results; in the language of game theory, the Demand-Led approach is the dominant strategy when it comes to performance.

So if Demand-Led Growth is such an obvious choice for performance, why is this even a debate in the first place? Why are advertisers voluntarily opting for sub-optimal results?

Balancing results vs. certainty

The answer is that the Traditional approach provides greater levels of certainty – and for finance teams, certainty has its own inherent value.

Once finance is comfortable with what the future looks like, they then have the basis for all of their decision-making. Certainty allows businesses to overcome inertia, and to get on with “doing business stuff”. Once you know how much you’re going to spend in marketing, you can lock in decisions around how you’re going to invest in R&D, how many people you’re going to hire, how many new stores you’re going to open, etc. etc.

It can’t be overstated how significant this is. For a finance controller, there are situations where it may be rational to sacrifice performance, if it means retaining higher levels of confidence about exactly what the future will look like.

So, the challenge for marketers then becomes this: is it possible to simultaneously deliver performance and control, rather than having to settle for an either/or tradeoff?

The answer is yes, it is possible – and we’ll explore how within the following chapter.

Operationalising your way out of the challenge

We’ve spent a lot of time with our most sophisticated clients to understand which techniques, mindsets, and processes are needed to support a transition to Demand-Led budgeting.

All-in-all, there are 2 main areas you need to consider.

Deciding what you want, and what you can afford

As a prerequisite, you need to know what you are expecting to drive from your paid search investment. What is the one metric that you most want to see increase as a result of your PPC spend? Whilst the channel will contribute to many KPIs, ultimately you have to select just one that you prioritise above all others.

Once you know this metric, you need to decide on the CPA or ROAS that you’re willing to accept. This calculation is a process that every business must go through, and should be worked backwards from your underlying business economics.

There is no single right way to do this.

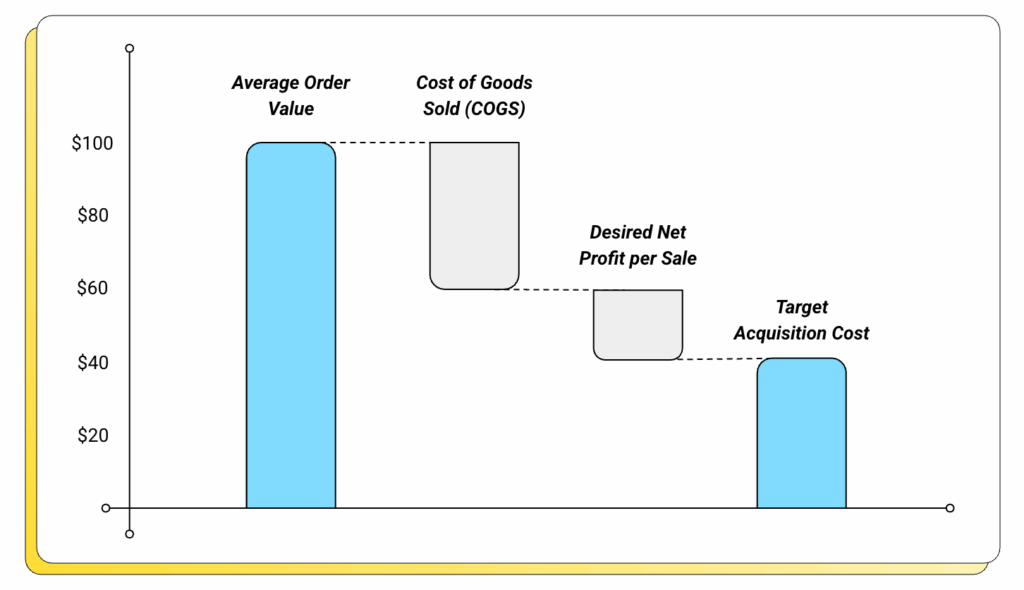

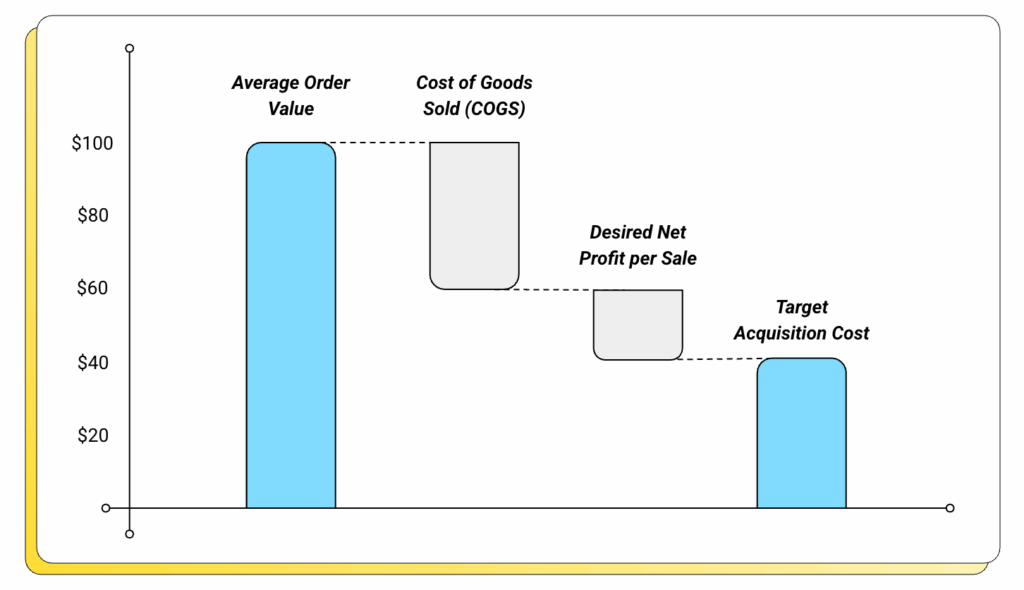

Deriving your media efficiency targets is a bespoke process for each company, and must be tied to your overarching commercial ambitions. To give a very straightforward example, imagine you’re a footwear brand who makes on average $100 in revenue per order. Of that $100, you know that 40% will need to be paid to suppliers as cost-of-goods sold. You also know that your business would like to generate a 20% net profit margin. Taking this into account, then your average cost per acquisition would be what’s left over, ie $40.

There are many other factors that you could consider incorporating into this calculation to fine-tune the number as precisely as you want.

However precise your thinking, what is crucial is that you do have “an answer”. If you cannot justify your media acquisition costs in terms of the unit economics of your business, then you are demonstrating negligence towards the company that you’re supposed to be working for. Don’t let that be you.

In an ideal world, you would also configure your bidding strategy so that your campaigns are directly optimising towards a monetary KPI – for instance, revenue, predicted lifetime value, or gross profit. This is known as value-based bidding. For certain businesses though, this isn’t always straightforward to implement, so do not let this be a blocker. As long as you know why your target CPA (or target ROAS) makes sense relative to the value of the customers you are targeting, then you have earned the right to consider implementing the Demand-Led approach.

Many organisations are already ticking this first box – but if you aren’t, then you must dedicate sufficient time towards working this out.

Bridging the gap from performance to certainty

This stage is equally important, and yet it happens so rarely.

Remember, finance loves control. They’re super risk averse. They’ve spent years in training to qualify for their role, and they’re good at their job. And here you are, about to ask them to deviate away from their tried and tested processes. Your role now is to hold their hand through the process: explain what you want to achieve, and give them enough confidence to sign off on you following a Demand-Led approach to Search.

But at the moment, none of your performance reporting builds this confidence, because almost all of it is backward-looking. This is a fundamental flaw. The reason for making decisions is to impact the future; the whole purpose of setting monthly budgets in the first place was to impose control & order on the future. Knowing only what has happened in the recent past doesn’t paint a sufficient picture of what is to come.

So then, what is the first thing you need to do to build confidence with finance? Forecasting. And I mean, a lot of forecasting. It’s not an exaggeration to say that, with many of our clients, we’re now producing somewhere in the region of a hundred micro-forecasts, every single week. (Thankfully, we’ve honed this process so that it takes no more than 30 minutes to produce all of those scenarios.)

If this is new to you, then fair warning: it probably won’t be easy to begin with. We’ve delivered literally tens of thousands of forecasts to clients over the years, and in doing so have developed a strong grasp of the core principles to use when forecasting in paid media – not to mention that we’ve built a range of template spreadsheets for this explicit purpose. But even still, every new client that we partner with requires a somewhat customised approach.

Once you have your forecasting process in place though, it unlocks conversations that were not possible before. It enables open forum discussions, led by marketing, in which you can present word-for-word:

- “Here is the performance we’re delivering right now;

- If we continue to operate as we are doing, then here is how much we are likely to spend, along with how much we expect to generate in Revenue / Profit / KPI-of-your-choosing;

- If there is some reason why this level of investment is no longer palatable for the company, then here are the alternative scenarios that we could move to if required.”

Normally, we’d view meetings without any follow-up actions as the scourge of the corporate world. But if you’re making a transition towards being a Demand-Led business, this is one of the few examples where the ideal outcome of the meeting is that nothing changes. If that’s the case, it demonstrates a good level of discipline in sticking to the previously agreed-upon CPA / ROAS targets. Simultaneously, you’ve still been able to communicate to finance a view of everything they need to know to reinstate their feeling of control: ie, you’ve told them what you think is going to happen in the future.

No less important than the forecasting processes you implement though, is the perception that you portray in these meetings. Remember the starting point that you’re working from: finance are not marketers. In fact, they probably view marketing as the worst team to work with. Over the years, they’ve seen countless marketers before you asking to spend loads of money, with no regard for fiscal prudence. I’m not making this up – these words are a verbatim quote from Brainlabs’ own finance team. If you want to be taken seriously when hosting these conversations with finance & commercial teams:

Don’t go in thinking you need all the bells & whistles. Don’t think that you’re putting on a magic show, or that you’re trying to “sell in” some crazy new idea.

Do play it straight & play it stoic. Earn trust by proving that you understand the numbers, and that you can give finance the information they want. When media performance is below expectations – as it inevitably will be at some point in your career – be realistic with where you are, and what levers you can pull to course correct.

Your role is now one of an investment manager, not just a PPC manager. Start acting like it.

Closing comments

Year after year, advertisers continue to let revenue opportunities pass them by as a result of being encumbered with processes and management systems that aren’t fit for the era of online search. As a result, this is costing brands to the tune of $107bn.

Every commercially-driven employee in your organisation – right the way through to the C-Suite – is invested in maximising revenues and profits. And through demand-led budgeting, marketers have a massive opportunity to step up and demonstrate leadership, and to shepherd the business into a new, more consumer-centric way of operating.

Good luck.

Appendix

Why budget constraints inflate your CPCs

Fundamentally, there are two settings that you can use to limit the amount you spend within Google Ads.

The first option is your campaign budgets. This is a number that a practitioner will enter into their campaign, which places a limit on the amount of money that the campaign can spend in a given day.*

The second option is your bid, AKA your bid strategy targets. Your bid determines how aggressively you enter into each ad auction, and influences your spend in two ways. Firstly, a lower bid will clearly reduce the price that you pay for each click. And secondly, a lower bid will reduce the number of impressions that you win, as well as your prominence on the results page – subsequently meaning that you will generate a lower volume of clicks. All pretty straightforward so far.

The key difference between these settings is that, whilst budgets will place a hard cap on your spend once you reach a certain point throughout the day, bids will only partially influence your spend. Ultimately, it’s a combination of your bid, plus the available search volume in the market, plus the behaviour of competitive advertisers, that will determine your spend.

Problems arise when your bids are too high relative to your campaign budget.

Let’s talk this through with an example. Imagine we’re running a campaign for which we’ve set a bid that results in an average CPC of $2. There’s plenty of search demand for the queries that this campaign is targeting, but we’ve set a budget cap of $100 a day.

When we reach 50 clicks within a day, the budget cap will automatically prevent us from entering any remaining auctions that day. This is not ideal.

Faced with this scenario, there are two alternatives we could consider. The most obvious one is to increase the budget. If you were happy with the returns you got from your $100 spend, then you could double the budget and expect to see exactly the same returns from the incremental $100 that you spend. In this scenario, you’d be eligible to enter into every single auction throughout the day.

However, this option would require you to invest additional budget – and on some occasions, in some businesses, that may be an option that is just simply not on the table, for whatever reason. So what else could we do?

The other option is to decrease our bid. Let’s say we could bring our avg. CPC down to as low as $1.50. We have now reduced the rate at which we’re spending money – but because the campaign had a surplus of auctions, this means that we now don’t exhaust our budget before the end of the day, and so we’re eligible to enter into every single auction.

And whilst we’re now less competitive, meaning we won’t convert auctions into clicks at the same rate as we were doing in scenario 1, we can still ensure that we achieve at least as many clicks as before, at an equal or lower cost.

When we stack those scenarios up against each other, we can see that performance in scenarios 2 & 3 is objectively better than what it was in scenario 1; we’re either getting more for the same, or we’re getting the same for less. There is of course a spectrum of other options, including scenarios in which we can get slightly more for slightly less. Hence budget constraints are damaging to both your traffic volumes, as well as your CPC efficiencies.

*Google can actually spend up to 2x your daily budget on any given day, but it will make sure it doesn’t exceed 30x your daily budget over a 30-day period. But this technicality is not important for the time being.

Evaluating the $107bn gap

Alphabet’s annual revenue from “Google Search and Other” advertising is $198.1bn1. Of that revenue, 90%2 ($178.3bn) is estimated to come from media spend on Search.

In the UK market, approximately 27%3 of media spend is budget constrained. This figure is assumed to be globally representative, leading to an estimate of $49.0bn spend globally that is budget constrained. (Note that we expect this is likely to be an underestimate, given the UK is typically one of the more digitally mature markets.)

The average ROAS that advertisers achieve with Google is 8:14. On average, non-constrained campaigns are expected to achieve a ROAS which is 30% greater5 than budget-constrained campaigns.

This works out as an incremental “ROAS headroom” of 2.19 being left on the table for budget-constrined campaigns. An extra 2.19 worth of ROAS, applied to $49.0bn of media spend, equates to a $107.4bn missed revenue opportunity for advertisers.

1Google 2024 Annual Financial Report

2Brainlabs internal data, extrapolated

3Google internal data, UK market

4Stat quoted by Google at GML 2025

5Brainlabs internal data, extrapolated